About seven years ago, as the world kept failing to achieve the Paris Agreement goals, I became more painfully aware that, as awful as climate change might be for me, it was far more frightening and real for my two children. Our failure was their future. I must have been one of millions to see this.

The most impactful decision I made was to stop taking long haul flights. These were (as they are for most people) the single biggest part of my huge carbon footprint. For decades, I had been in the habit of flying to the US about once a month on average. To Singapore a few times a year. India? Australia? Sure. When I estimated my carbon footprint, my horror of the climate future stared back at me and became very real.

So I stopped.

Habits are hard to break. We become inured to both their benefits and their costs. For me the benefits were interesting, well paid work, seeing friends, working in diverse cultures and meeting great colleagues. That it was a habit inured me to its costs. Habits are like that, instilling wilful blindness to actions that, viewed differently, are appalling.

When I made the decision, I accepted the fact that my income would decline; I decided that was a price worth paying to be able to look my children in the face.

What I didn’t expect were the other benefits that flowed from my choice. Now when I explain to companies why I can’t fly to speak at their conference, I’m heartened by the degree to which they welcome this conversation, relieved even to be able to talk about a topic that lies latent in their organizations all the time. That was unexpected. So too has been the number willing to host a virtual event instead, happy to save money and to feel good about it.

I’ve developed more business in Europe; there was plenty of diversity on my doorstep. I have more time to write, more time too to support climate champions inside companies whose impact can be greater than any private individual decisions. Figuring out the intricacies of European trains is more complicated than booking flights but has also prompted a discovery: that getting to a destination is part of the pleasure, which air travel never was. I do not miss jet lag.

But most of all, this decision has made me think about habits: ways of life that become so routine that we cease to think about. Habits are based on assumptions that we don’t question. Assumptions like: There is no other way. It’s cheaper, faster this way. Everyone does it. It’s easier. I like it. Nobody gets hurt.

Is easy always better? Is faster always best? Are you sure nobody gets hurt? These questions crop up in connection with AI all the time, but they are just as relevant to every habit we inherit or develop.

It’s become orthodoxy to argue that changing habits is always hard. In management circles, the common analogy is with changing the hand you write with. It is hard, certainly. But how much of the difficulty derives from the fact that, in the exercise, there is reason to change? It’s just an exercise. If I had to change, I’d manage—but what else might I discover, about the world or within myself?

Sacrificing long haul flights hasn’t been hard; to know the cost and still continue would have been excruciating. Many other changes have followed as I’ve found alternative pleasures—but also discovered my own tolerances and failings. Those difficulties contain meaning, learning and value too.

What habit might you want to change today?

To Go Deeper

The big beasts who have thought deeply about habit include Aristotle, Spinoza, Hegel, Kierkegaard, Ravaisson, Nietschze and Proust, who argues that if a habit is second nature, then it prevents us knowing our first.

The contemporary philosopher Clare Carlisle has written wonderfully on this.

For the joy of it

The other day I revisited Christchurch Cathedral in Oxford. This is one more step towards completing a project begun many years ago, when we decided to visit all the cathedrals of England and Wales. Our daughter was off to university and I feared we would now spend weekends working. A habit to fend off before it became entrenched.

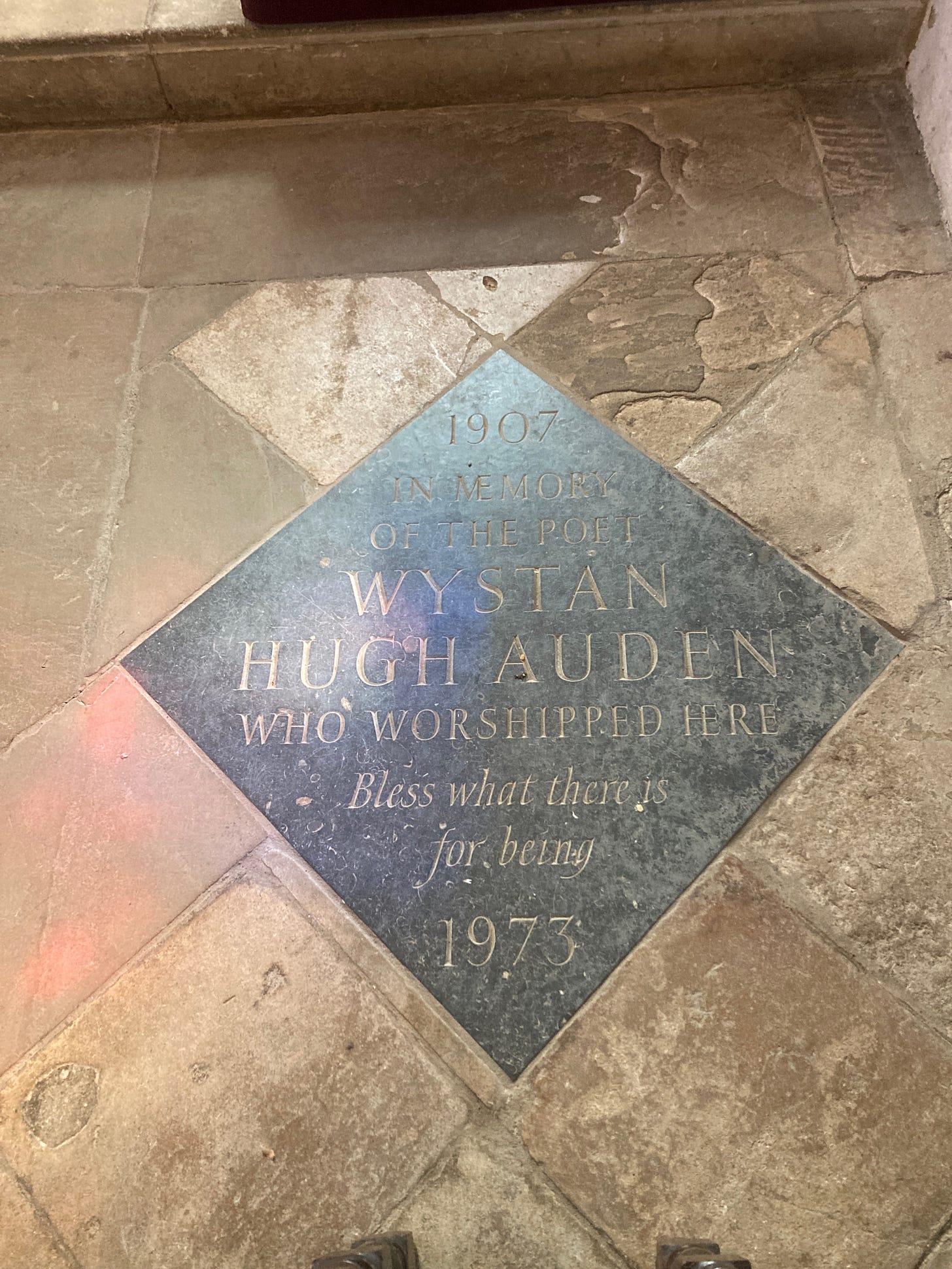

With only 4 more in England and 2 in Wales remaining, the cathedral project has been a fantastic way to visit places we didn’t know ,while gaining some insight into the state and status of the Church in the UK. (A future post perhaps…) A lovely surprise in Oxford was to find a memorial to W.H. Auden inside Christchurch where, as Professor of Poetry, he attended services regularly. A whole aspect on a favourite poet, sitting quietly in this small, ancient space. Even noisy tourists couldn’t spoil it.