PURPOSE IS POINTLESS

Johnson & Johnson book poses questions about institutions that Purpose cannot answer.

Over the holidays, I posted nothing because I suspected my readers could use a break—and I certainly needed one. And then my first post of 2026 turned out to be unavoidably longer and more difficult than I’d foreseen. So: apologies for the radio silence. Normal service has now been resumed. And thank you for your patience.

On August 19, 2019, 181 CEOs of America’s largest corporations overturned a 22-year-old policy statement that had defined a corporation’s principal Purpose as maximizing shareholder return. Instead, they now declared a new Purpose: asserting that companies should not only serve their shareholders but also deliver value to customers, invest in employees, deal ‘fairly and ethically’ with their suppliers, engage in ‘sustainable practices’ and support the communities in which they operate. And it committed to ‘transparency and effective engagement’ with stockholders. A radical revision of Milton Friedman’s shareholder doctrine, which held that the only Purpose of a business was to make money for shareholders, this new statement was heralded as a sea change in the world of management. Now the business of business was to deliver the economy that all Americans deserved, one that allowed “each person to succeed through hard work and creativity and to lead a life of meaning and dignity.” Purpose had ridden into town on horseback and Purpose became the story that business would tell about itself from now on. For many who had long fought for a wider, more humanitarian industrial outlook, this seemed like a new dawn.

But business has a nasty track record of taking perfectly serviceable words and stripping them of meaning, so passion for Purpose fell right into line behind Mission (1960s and 70s) Vision (1980s) and Values (2000s) statements that had had their moments in the sun too: at first full of sound of fury but finally signifying nothing as abstract nouns proliferated and everything remained remorselessly the same. At the time, my railing against yet another buzzword that could mean anything—and therefore meant nothing—was met with a quizzical response: who could possibly not embrace Purpose? In no time at all, everyone became fluent in doublethink and the Purpose bandwagon was on its way, trailing trite motherhood statements across the corporate landscape. War was Peace, Freedom was Slavery, Ignorance was Strength and Profit, it now seemed, was Purpose.

Why so cynical? Because I’ve now read No More Tears: the dark secrets of Johnson & Johnson by Gardiner Harris.* I admit to a strange appetite for what I call ‘business car crash books’: a literary diet that led to my writing Wilful Blindness. I am endlessly intrigued by how large organizations full of good people go bad, and inquisitive about underlying causes. Paradoxically this is because I am an optimist: I believe organizations can and must do better and that most workers want to do a decent job. But No More Tears is too shocking, heartrending and epic in its implications, not to force a rethink. I’m also puzzled by the silence that has mostly followed its publication. As yet I’ve met no Purpose-champions who have read it, nor any CEOs.

Except No More Tears is not another car crash book. Johnson & Johnson still features in the list of the World’s Most Admired Companies and continues to be one of only two corporations on earth with a triple-A credit rating. Its former CEO has won numerous awards and now sits on the boards of JPMorgan Chase and Apple. It was when he served as Chair of the Business Roundtable Corporate Governance Committee that the Purpose repositioning came out and it appears to derive much of its language and ethos from one of the earliest of such statements: Johnson & Johnson’s 1943 Credo.

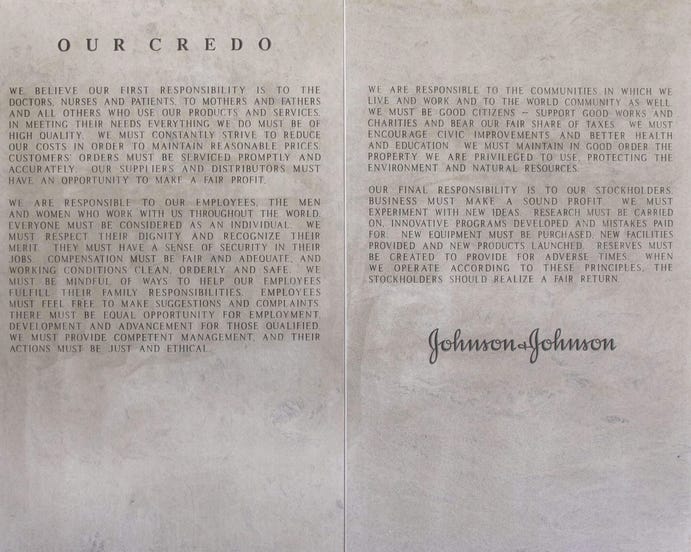

Many corporate Purpose statements these days – they are ubiquitous – are drafted, published and ignored. But this wasn’t the case at Johnson & Johnson. It wasn’t just carved in stone at corporate headquarters. According to Harris, all important meetings considered the Credo; annual surveys required that employees report how closely they adhered to it. The Executive Committee met with 2,000 employees to discuss and try to improve it. And yet Harris’s research into the company has made me revisit my perennial questions about leadership and language and leaves me wondering what we do when both fail.

The story of Johnson & Johnson starts gently enough, describing the emotional and nostalgic attachment that consumers developed for its products. Like most Americans, Gardiner Harris grew up believing in J&J: the largest health conglomerate in the world and a byword for caring, it seemed the perfect proof that profit and Purpose were made for each other. 130 years old this year, its modern image as an ethical, benevolent, Purpose-driven business was epitomized and mythologized by the Tylenol news story of 1982. When bottles of the drug were found to be contaminated with cyanide, killing at least 7 people, the story became, Harris writes, “one of the most extensively covered news events since the assassination of President John F. Kennedy almost twenty years earlier.” Far from tarnishing the company’s image, the massive coverage made it: at a cost of $100 million the apparently immediate, uncompromising and altruistic decision to remove 30 million bottles of Tylenol from stores was held up as a model of corporate citizenship: how, in a crisis, business could do well by doing good.

What no one saw or apparently interrogated was that for three years the company had received over 300 complaints about contaminations. They had, according to Harris, already been discussing tamper-proof packaging (which is why they were able to act so quickly after the crisis.) And although the legendary PR story highlights the speed of the response, Harris found that J&J had also resisted the full recall for a week.

But chief among the corporation’s iconic consumer products was Johnson’s Baby Powder, a product that outsold all its competitors. Many of us still associate its scent with our childhood. But in the 1960s research into the carcinogenic properties of asbestos soon prompted further investigation of talc too, with which it shared so many mineralogical similarities as to be almost indistinguishable. By 1968, scientists revealed that all consumer talc products contained traces of asbestos and a clinical director at J&J warned that the corporation might wish to consider “the defensibility of our position.” According to Reuters, “from at least 1971 to the early 2000s, the company’s raw talc and finished powders sometimes tested positive for small amounts of asbestos, and […] company executives, mine managers, scientists, doctors and lawyers fretted over the problem and how to address it while failing to disclose it to regulators or the public.”[i]

By 1989, most producers of baby powder had replaced talc with cornstarch. But not J&J. In 2004, it was the company’s talc suppliers who started placing cancer warnings on every bag of talc they delivered to their corporate customers, but no such warning made its way onto consumer products.[ii] By 2008, at least one company executive was sufficiently uncomfortable with the traces of asbestos in the talc that he proposed moving it to a different category area in stores. He didn’t mind selling talc, he just didn’t think that selling it on the baby aisle was okay. Citing the Credo, he made all kinds of positive suggestions—reformulating the product, renaming it, even developing it as a product for adults. Acknowledging the ‘cost implications’ he argued that this could be a positive move. Apparently nothing came of his proposal; the executive remained at the company for another seven years.

On reflection, one of the many striking elements of this email is that its author seems concerned primarily about babies; did nobody consider that if talc is unsafe for use on or around babies, it might hurt adults too? Adults like Toni Roberts, who used J&J’s talc after a shower, across her chest, on her inner thighs and legs, on her shoulder, elbow, chest and knee pads and skates of her two boys. She even sprinkled it on her carpet to reduce the smell of her dog.

In 2013, J&J lost its first Baby Powder cancer lawsuit. More cases followed until, on July 19, 2018 a jury awarded one of the biggest civil judgments in history[iii]: $4.14 billion in punitive damages. Three months later, Toni Roberts died of ovarian cancer. When an appeals court reduced damages to $2.1 billion, it nevertheless took pains to point out that the “Plaintiffs proved with convincing clarity that Defendants engaged in outrageous conduct because of an evil motive or reckless indifference.”[iv]

Not until May 2020 did J&J announce that it had stopped selling talc-based Baby Powder in the US and Canada; the rest of the world had to wait until 2023. As recently as 2024, after billions of dollars of awards against it, the company continued to insist that its baby powder was safe. If the Credo was supposed to be a moral compass, it didn’t prove great at giving direction.

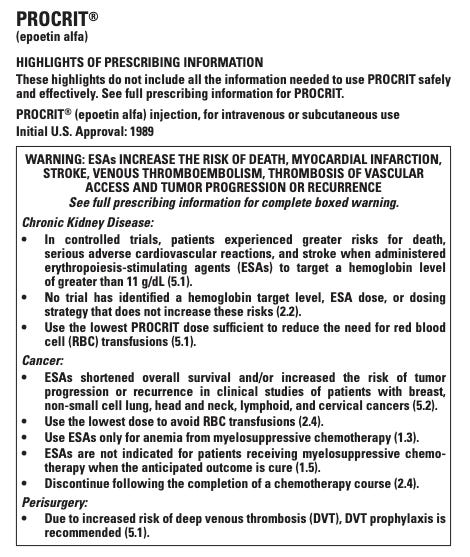

Harris’s charge sheet mounts, slowly but steadily. Most cases are complex and, for legal reasons, are too difficult to summarize. But as J&J expands from household staples like baby powder and Tylenol, into prescription drugs and biotech, then medical devices and vaccines, the vulnerability of users ramps up together with profits and risk. EPO, a drug administered to cancer patients whose treatment had made them anaemic, was found to grow their tumours. By 2002, it was one of, J&J’s best-selling drugs. In 2007, after numerous studies indicated that EPO could shorten life, the FDA required that the label include a warning that the drug should not be given to any patients “when the anticipated outcome is cure.”[v]

Yet despite civil and criminal prosecutions yielding billions of dollars of fines, the EPO drugs continued to be sold. “It became,” Harris writes, “the first big biotech franchise in history, made more than $100 billion in sales, and contributed to the deaths of perhaps hundreds of thousands of people.”

“We are responsible to the communities in which we serve.” The authors of the Credo may have believed this, but just citing their Credo didn’t make it come true. Intended to provide a ‘guiding light’, patients were in the dark. Harris’s accounts of J&J’s Risperdal (an antipsychotic used on elderly dementia patients and children), hip implants and vaginal mesh carefully challenge the company’s statement that its “first responsibility is to doctors, nurses and patients and to mothers and fathers and to all others who use our products and services.” That the documents underpinning so much of the narrative are now online provides even more detailed close-ups.

Reading No More Tears took me back to the years when I was researching Wilful Blindness. All the telltale patterns of wilful blindness are here: obedience, conformity, conflict-aversion, groupthink, the competitiveness of sales cultures, bystander behaviour and the enormous influence that thinking about money has on our attention and decision-making. This is familiar territory.

But what came as a big surprise was to learn that J&J became the largest supplier of the active ingredient in opioids in the United States. After buying a Tasmania-based opioid production company in 1982, they engineered a ‘super-poppy’ (named Norman) that produced high levels of thebaine, the essential precursor of oxycodone. This work enabled J&J to become the dominant producer of the crucial ingredient in Oxycontin.

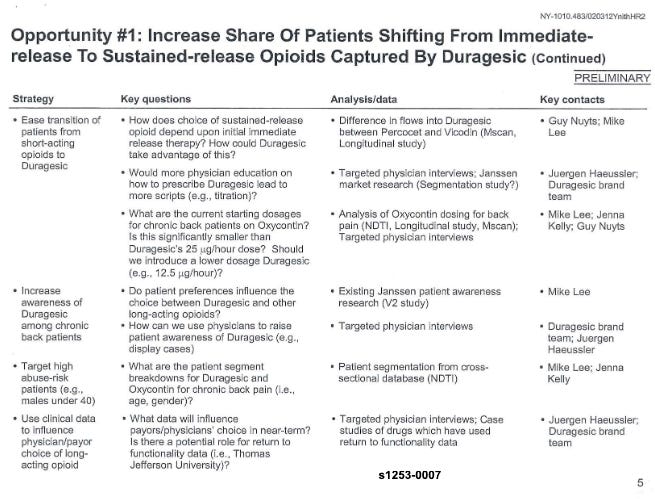

As well as supplying major opioid producers, J&J competed with its own product, Duragesic, and sought advice from McKinsey on gaining and retaining market share in a now highly competitive market. The consultants’ advice: “Target high abuse-risk patients.”[vi]

Operating both as competitor and supplier to Purdue, the consequence of J&J’s opioid activity was significant. “J&J soon became the largest supplier of the active ingredient in opioids in the United States, responsible for providing enough for about half of all opioid pills sold. Among its American customers was Purdue Pharma.”[vii] Harris cites Andrew Kilodny, whom he describes as the world’s foremost expert on the opioid crisis: “J&J was clearly the kingpin of the opioid epidemic, not Purdue Pharma. They were not only marketing their own branded opioids but were supplying almost every manufacturer with the crucial active pharmaceutical ingredient.” [viii]

With good reason, Harris rages at the degree to which, compared to Purdue and the Sacklers, J&J appears to have sustained no reputational damage from its involvement in the tragedy of America’s opioid epidemic. But the Purdue story has a name, a family, to play the part of the villain. Harris’s story, by contrast, meticulously traces a complex web of companies, executives, salespeople, scientists and regulators. It’s a tougher tale to tell and to follow—and one all too easily ignored by under-funded or dependent regulators and media organizations. Both Harris and Kilodny argue that one major reputational advantage J&J had was its brand. What with the Credo and the great Tylenol case study—who would imagine anything bad could come from baby-kind Johnson & Johnson?

There might not have been any story at all but for whistleblowers. Harris writes that most of the cases brought against J&J originated with them. As is so often the case, whistleblowers are rarely natural troublemakers but begin as true believers in the Purpose—until they find the cognitive dissonance between Purpose and reality too excruciating to bear. The huge risks these individuals take is usually an expression of disillusion and grief. Others providing Johnson with critical information may not even have worked for J & J. Remarkably, he secured Grand Jury documents which are typically sealed indefinitely, which implies that the tragedies he relates shocked many consciences into action. His conclusion is bracing:

“For all intents and purposes, Johnson & Johnson was a criminal enterprise. Indeed, mafia families get a large share of their income from strictly legal activities. But no mafia outfit ever consistently targeted the kind of vulnerable people that J&J exploited. And if one of the most admired corporations in the world is in reality a criminal enterprise and a killing machine, what else are we missing? How many other killers are out there?”

Harris lets no one off the hook—government, regulators, media, doctors, hospitals, insurance companies, distributors, the legal system—and in comparing J&J with its competitors, he acknowledges that J&J was not always alone in many of its practices. While nobody knows the total number of deaths caused byAmerican for-profit healthcare, he estimates it as “certainly in the millions—more than the combined American toll from every war since the birth of the United States.” [ix] Necessarily his recommendations for correction and improvement run broad and deep and their goals are hard to fault. But after decades of epic moral failure, it’s hard to imagine individual reforms budging the needle.

After the collapse of Enron, at least the company ceased to trade, its CEO Jeff Skilling went to jail for twelve years, was fined $45,000,000 and barred from serving as a company director. (Enron, some may remember, had no Credo but proudly boosted its values—Communication, Respect, Integrity and Excellence—along with its famous Post-It notes quoting Martin Luther King: “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”) In all the corporate scandals and failures that have followed, we’ve seen few, if any, comparable consequences, while corporations have continued to trade on the now questionable assumption that they will have learned their lesson. Has silence about the things that matter become business as usual?

In the U.K., successive institutional failures ushered in a law of Corporate Manslaughter but this has no power to punish individuals, it can only levy unlimited fines. Just 3 convictions have been obtained since the law was enacted in 2008. Corporations, it would appear, have wide licence. In the U.S., as the law stands today, corporations may enjoy the freedom of speech of a person, but with no equivalent responsibilities. In the context of AI and genetic engineering (one of the pioneers of gene editing sits on J&J’s board), the danger inherent in such over-arching power has never been so great, while the current political mood shows little appetite for reform.

I can’t help but be puzzled by the rather tame reviews the book has received. Few register any real shock or surprise. Nothing (bar Andrew Hill’s review in the FT) alerted me to how shocking the book’s revelations are. Could that be because we have already lost the fight? After Enron, WorldCom, Boeing, Volkswagern, McKinsey, WellsFargo, Theranos, Facebook, big tobacco, big pharma, big tech and big food, or, in the UK, after the Post Office, Grenfell, the Met Police, NHS scandals and RAAC, have we all normalized business deviance? I remain a defiant optimist but I keep thinking about all the J&J people who were not whistleblowers: do they wonder about their enabling roles? Do they ask themselves what happened to their critical thinking—and, if they do, how do they explain what happened?

What I can’t do is is read No More Tears believing that Purpose or any other fancy face-saving formulation of business buzzwords can have impact on a business culture sufficient to withstand the temptations of profit. But profit alone cannot be the sole culprit here. Widescale abuses of power in organizations whose only business is (or should be) the improvement of human life—charities such as Oxfam, Save the Children, institutions such as the Catholic Church and Church of England—cannot but make any serious student of leadership and management stop and ask: after a century of research, authorship, debate and (apparent) reform, have we learned nothing? What, seriously, can we offer now that defies the cynical conclusion that these businesses and institutions are all the same? And what credible hope can we offer younger generations that working inside organizations will not infect them with wilful blindness? If J&J is one of the most admired corporations in the world, what must the rest be doing?

At the very least, we need to stop reaching too quickly for a consoling bundle of magic words. Purpose has become a smokescreen, a disguise. Pretending to, or encouraging a belief in, a higher value system beyond profit is a feint. Deceptive and mind-numbing at worst, decorative and distracting at best, it is a displacement activity which looks like conscience but cannot induce it. We will get nowhere until business can forswear abstract nouns and learn to use language that is practical and tangible. We also have to call out the suspects that keep making repeat appearances at every crime scene: Scale, Competition, Speed and, yes, Purpose: the over-zealous belief in an organization so devout that it blinds followers.

Instead, let’s start asking adult questions that do matter: not what the profits are, but how they have been achieved and at what cost to individuals, employees, to society at large. Every decision has trade-offs; let’s stop ignoring them but instead identify them to see just how many we can stomach. If we cannot have that conversation, then all the Purpose-speak in the world is a fairy tale and all its believers merely credulous children. And we cannot have that conversation unless or until we take language seriously as reality instead of camouflage.

It is time to acknowledge that we are lost, confused or corrupted. Until or unless we can contemplate the idea that many of the foundational theories of business not only do not work but frequently backfire, we will not counter cynicism with anything but hollow words and deceptive fantasies. It strikes me now that businesses are littered with the zombie theories of decades gone by: beliefs that continue to prowl corridors of power long after they should have died. In the next few months, I’ll drag some of those into the light and interrogate them. After reading No More Tears, it’s hard for me to think of any that don’t demand re-examination. Maybe you can propose some. But please let’s abandon mantras and embrace scrutiny. The dead will thank us, and the living too.

If You Want to Go Deeper

Do read Harris’s book. He writes well and it is a breathtaking read. And we need to know this stuff.

If you’re buying it - go to Bookshop.org to support independent bookstores. This month, they have a new series of books for the new year which I’m delighted to say includes my book, Embracing Uncertainty, and you can use the code NEWBOOKS26 to get 15% off any of their New Year recommendations. But please read Harris’s book too.

For the Joy Of It

Enough words. Here is a gorgeous piece of music, completely new to me: Jeu sur la Symphonie Fantastique. I love Berlioz’s original but this interpretation by Ballaké Sissoko got my day off to a glorious start.

*Note: All the information about Johnson & Johnson was taken from the book NO MORE TEARS by Gardiner Harris, published by Random House in 2025.

[i] P.63

[ii] P 61-2

[iii] P. 80

[iv] P80

[v] P 157

[vi] P. 243

[vii] P. 236

[viii] P. 251 State of Oklahoma v Johnson & Johnson et al. Trial transcript, June 17, 2019. Dr. Dr. Andrew Kolodny is the Medical Director for the Opioid Policy Research Collaborative at the Heller School at Brandeis University and he serves as President of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing, an organization that advocates for more cautious opioid prescribing.

[ix] p.342

I think that the key to moving forward is to understand what it means to own an organisation..at small scale, be it a family or a community the issues are contained but once scaled it gets to be contestable then unknowable. Instead of too big to fail, we need to consider too big to manage and too big to care and possibly others. Instead of antitrust we need to promote anti mistrust

As long as I can remember J & J was held up as a by word for wholesome healthy product. Bloody hell!